We went to Auschwitz yesterday. The feeling of going there, particularly before we actually arrived, was, for lack of a better word, surreal. As the kilometers click away, and you get closer and closer to the place, the pictures and movies you have seen add weight, and you feel that weight upon you, kilometer upon kilometer, the closer you get.

Unfortunately, the countryside does not feel the weight of the place. Seven kilometers out, we ran across a beautiful restaurant with an old pre WWII airplane outside as a decoration. The plane looked like it could easily still fly, and I would have been interested in stopping, had we not been so close to Auschwitz.

Two kilometers out, and we were in the Polish city of Oswicim, which the Germans renamed ‘Auschwitz’ upon occupation (the Poles still call it Oswicim). The camp was then named after the city. We passed a large shopping mall and I was confronted with the fact that people live here, in beautiful houses and apartments, not oblivious to the fact that at least 1.3 million people died nearby, but not feeling the weight of those deaths either. To those who live and work in and around Oswicim, the place is simply home.

We turned the corner onto the street Auschwitz is on. Auschwitz II – Birkenau needed another turn to the right, while the main museum at Auschwitz I, was straight ahead.

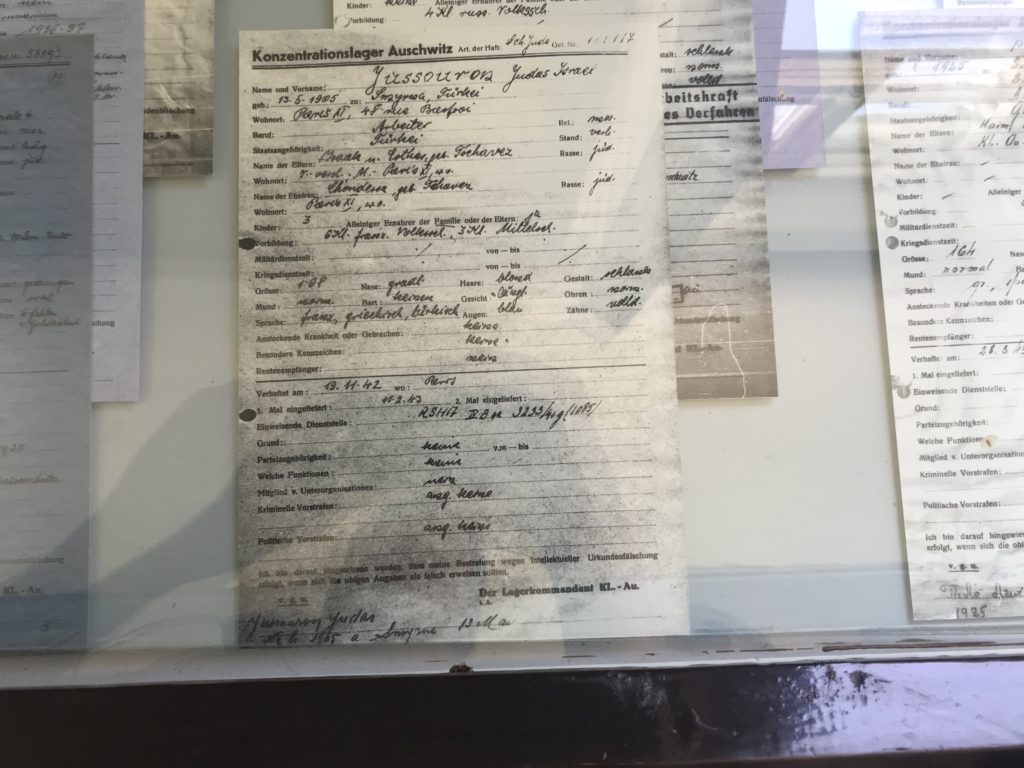

I should probably stop here and give a little history. Auschwitz was not just one camp, but a large complex of camps including three main camps, and 45 satellites. The original Auschwitz was a work camp, built in 1940 to house Polish political prisoners (I saw the sight where the first 750 political prisoners were shipped out, from nearby Tarnow, just the previous day). But Auschwitz was perfectly located in the center of the German Eastern holdings, making it an ideal location for the ‘final solution’ once the ‘final solution’ was put in place. This required building new camps, and particularly Auschwitz II – Birkenau.

The original Auschwitz was built at an old Polish military base, and the buildings were designed to house soldiers.

The infamous ‘Work will set you Free’ sign hangs at the original Auschwitz. I don’t believe the Germans had any intent of letting any of the people who went through that gate survive, but certainly they were told that if they worked hard, and accepted the Nazi occupation, they could one day return home.

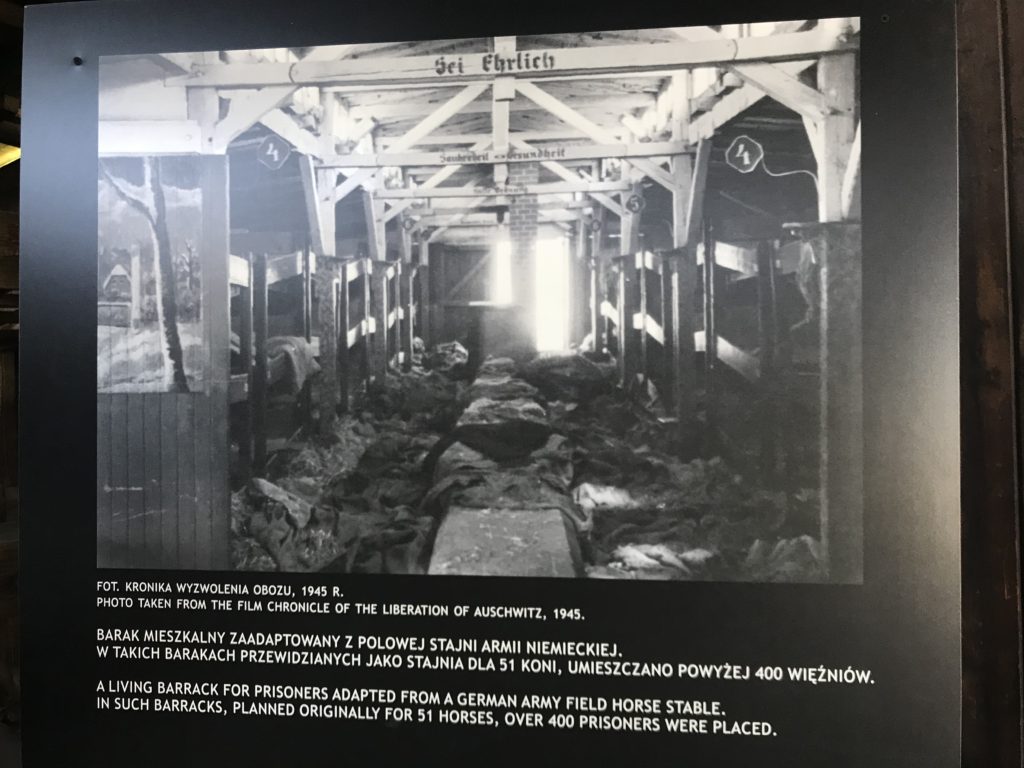

Auschwitz II – Birkenau is a separate camp, but it is only a three kilometer walk from Auschwitz I, designed to hold 90,000 people at a time (it held as many as 250,000), absolutely dwarfing the original Auschwitz. It is this camp people generally think of when they think of the holocaust, and rightfully so – more people died at Auschwitz II – Birkenau than at any other Nazi site.

We drove past the short road leading to Auschwitz II – Birkenau, and headed toward the main museum, at the original camp. Across the street from the original camp, there were restaurants and hotels, which makes sense, considering the millions of people who visit Auschwitz every year. But it does not gel with the feeling one has when driving to Auschwitz. Right across the street are two hotels, a pizza parlor, a burger bar, and an ‘art deco’ restaurant. It makes no sense. It’s like being outside Disney’s Magic Kingdom. And yet, as out of place as it feels, there it is, and it is quite practical when considering the millions of people who visit every year. Auschwitz is like a Disney park in terms of the number of visitors – it just is not like a Disney park in terms of content. It’s like a theme park whose theme is death.

It feels like a theme park when buying tickets too. We waited in line for over two hours.

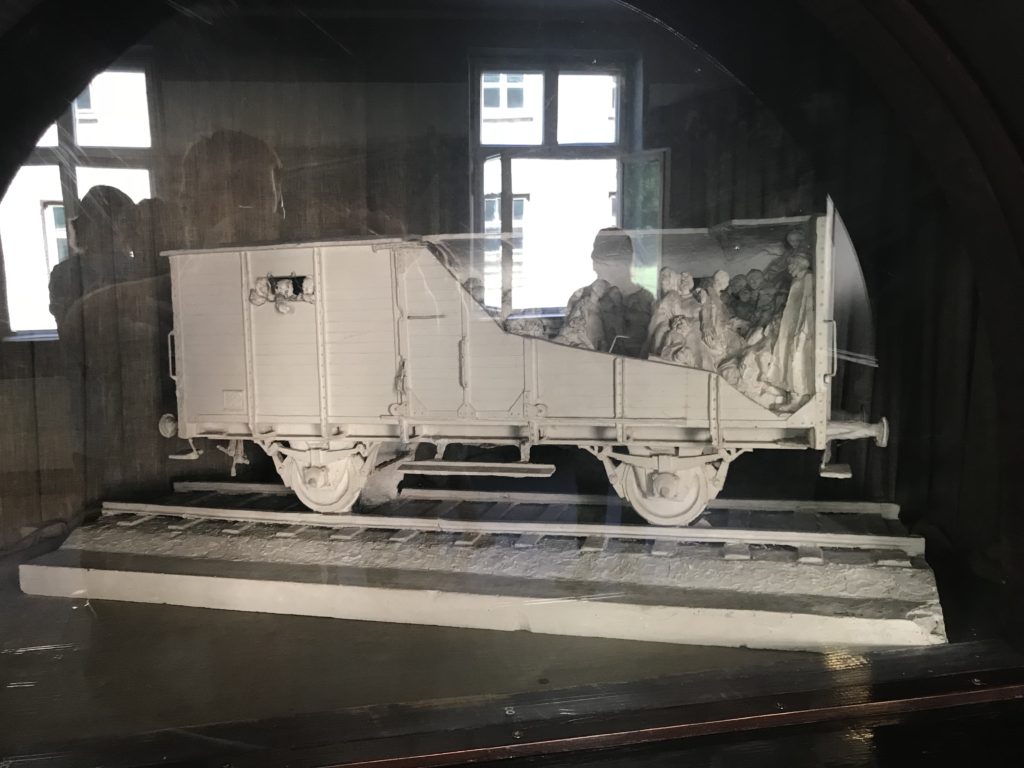

Ironically, once we got to the ticket booth and got tickets, our tour started fifteen minutes later. It’s almost like they wanted us to stand in line for two hours before buying a ticket – as if they did not want us to buy a ticket and relax for two hours before going in. It is almost as if they wanted us to be tired, and though they can never make someone as tired as the 1.3 million people who arrived at Auschwitz by train (some of whom were crammed like cattle into box cars for up to ten days), they are damn well going to try. You enter the museum wishing badly to sit down.

You do not sit down.

I read this to my wife after getting to ‘you do not sit down,’ and she had two comments. The first was that you do not go to the bathroom either. There are no bathrooms outside of the entrance. I had to use the restroom about an hour in to our wait, and I ended up going to the burger restaurant across the street. Problem solved.

My wife’s second comment was that she does not blame the city around Auschwitz for having a mall, restaurants, and everything else a city would normally have. And of course my wife is right – right on two counts.

First she is right because cities do hold all of those things, and with millions upon millions of people visiting Auschwitz every year, businesses will crop up to support those visitors. Businesses will also crop up to support the people who live around Auschwitz. It may feel weird to the visitor, but it feels normal to the people who live around it.

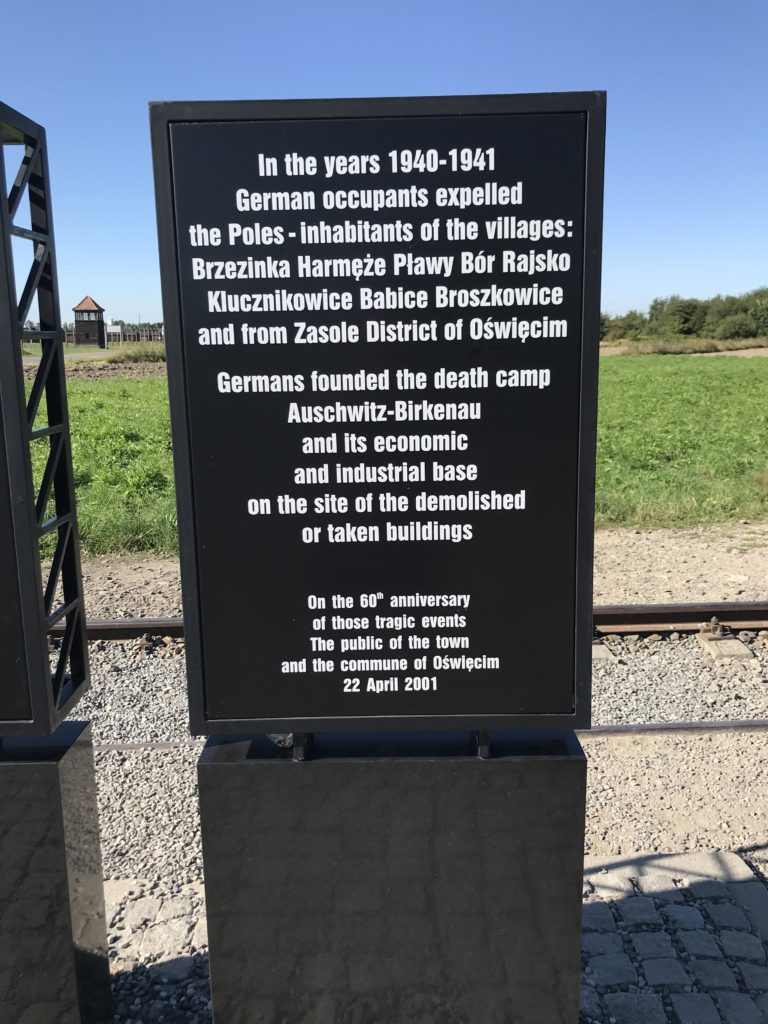

Second, she is right because what happened at Auschwitz was not the fault of the Polish people. The first people who were sent (and died) there were not Jewish, but were Polish political prisoners – basically anyone from Poland who had any political clout. Some people act today like the Germans asked to come in, and needed Poland’s permission to build Auschwitz, but the Germans took over Poland very much against Poland’s will. Poland fought invasion harder than did France, and Germany’s plans for Poland after the war was to exterminate the Polish people by forcing them to farm the land, while taking everything they produced, gradually replacing the Polish people (who would starve) with Germans. The Nazis liked the people in Poland who were ethnic Germans, but Germany wanted to exterminate Poland of all people who were not German, such that Germans could take over the land.

Understanding German plans for Poland requires understanding two German words. The first is ‘volk,’ which means ‘the German people,’ and by ‘German people,’ it does not mean people living or born in Germany, but all ethnic Germans everywhere in the world. The other word is ‘fuhrer,’ which is generally translated into ‘leader,’ but which really means ‘living embodiment of the German volk’. Germany looked at Poland as libenstraum (‘living space’) for the volk, and the Fuhrer, as the living embodiment of that volk, felt not only justified, but compelled to kill off all blood that was not ethnic German. Poland is on what is primarily an open plain between the Germanic and the Slavic peoples, and the Polish people are a Germanic/Slavic mix. Hitler wanted all but pure Germanic Poles dead.

Parts of Poland were ethnically German, and those parts of Poland supported Germany – giving two full divisions to the SS before the end of the war, but those ethnic Germans were acting for Germany rather than for Poland, and were concentrated in small parts of Poland that had, for 150 years prior to WWI, been part of Germany. The vast majority of the Polish people were from parts of Poland that had for 150 years been a part of Russia, and were considered sub-human by the Germans. These people were in no way complicit in German atrocities.

Israel seems to think Poland should apologize, as Germany has, for the holocaust, but Poland was a victim. Conservative estimates say that between 130,000 and 140,000 non-Jewish Poles were sent to Auschwitz (along with over 200,000 Jewish Poles), and it is incredibly insulting to ask the Polish people to apologize for atrocities that were committed against them rather than by them.

Israel and Poland are both victims of German aggression. Israel should embrace Poland. The Poles no more owe an apology to the Jewish people than the Jewish people owe an apology to themselves.

Poland was also a victim of the Gulag Archipelago, having fallen under Soviet rule after the war, with at least 1.8 million Poles sent to Siberian gulags by Stalin alone.

My wife’s second point then was well taken. The Polish people have been persecuted by Germany and Russia, for hundreds of years.

Still, when one is going into Auschwitz, it feels like there should be a zone around the place where nothing happens, like there is around Chernobyl, where the land is too radiated to live. Seeing abundant life around Auschwitz – well.. It just struck me as emotionally odd. I’ll leave it at that.

Another thing to dispel is the idea that the German concentration camps were somehow unique to German occupied lands. The fact that the Germans targeted a specific religion (and specific ethnicities) was unique to Germany, and the German people, generally being excellent engineers, were very efficient at killing, but while Hitler killed roughly 12 million people (6 million of whom were Jewish), Stalin killed 20 million Russians, and Stalin was but one of many Soviet Premiers, all of whom ran a gulag system that would have made Hitler envious.

In Stalin’s case, the 20 million number does not include 14 million Ukrainians who were systemically starved to death in the 1930s, nor the 1.3 million Poles sent to Gulags. Chairman Mao, in China, killed over 100 million of his own people.

Let me be absolutely clear on something that is historically incontrovertible: everywhere communism has been tried, it has lead to genocide. Stalin and Mao were only the worst offenders in terms of raw numbers – largely because they ran the largest communist countries, by population. Other communist leaders were even bloodier in terms of percentages. Pol Pot, Castro – they all committed genocide.

Communism does not work, and attempts to make it work mean genocide, always.

That last sentence will be controversial. So be it. If you are a communist, or you have a tee-shirt with a picture of Che Guevara in your wardrobe, you support a political ideology that is at least as bad as was Nazi Germany, and Auschwitz exists to warn the world about you.

Auschwitz is not just about Nazi atrocities, but about every instance of mass, organized death, and the world has seen that many times. There is a plaque in the main entrance to the museum that reads, ‘Those who fail to learn from history are bound to repeat it,’ which makes this case very clear. Auschwitz exists to remind each and every one of us that we have the capacity to commit such acts of horror – that good and evil are choices, and are choices human beings often make poorly. Papa Doc and Baby Doc Duvalier made the wrong choice in Haiti. Radovan Karadzic made the wrong choice in Bosnia.

To consign Auschwitz to the past is to ignore the cases of genocide occurring right now, today, such as in Myanmar, where the Rohingyaare being exterminated; Sudan, where the Nuer (as well as other ethnic minorities) are being exterminated; Iraq and Syria, where the Christians and Yazidis are being exterminated; the Central African Republic, where Christians and Muslims are being exterminated; and Sudan, where the Darfuris are being exterminated. How can we as a people pretend that we have learned from Auschwitz when similar atrocities are occurring right now, even as I type this, in at least five nations, and where hundreds of millions have been killed in death camps after Auschwitz was liberated, in many cases by the same Soviet Union that liberated Auschwitz? It is a little known fact that some of the 7,500 people liberated at Auschwitz later died in gulags in Siberia. We have a plaque commemorating the liberation of Auschwitz, but where is the plaque calling out the Soviets for killing some of the survivors?

We have learned nothing, which is why genocide is occurring right now, and we do nothing, and which is why large numbers of American youth commemorate communists.

We have learned nothing, which is why Auschwitz makes me angry more so than sad. I am sad, obviously, because of what happened there, but I am also angry, and unspeakably so, because, as I saw the vastness of the complex at Auschwitz II – Birkenau, I could not only envision the faces of the people who died there, but also the faces of the people who have died since, and who will die today, because you and I have collectively learned nothing.

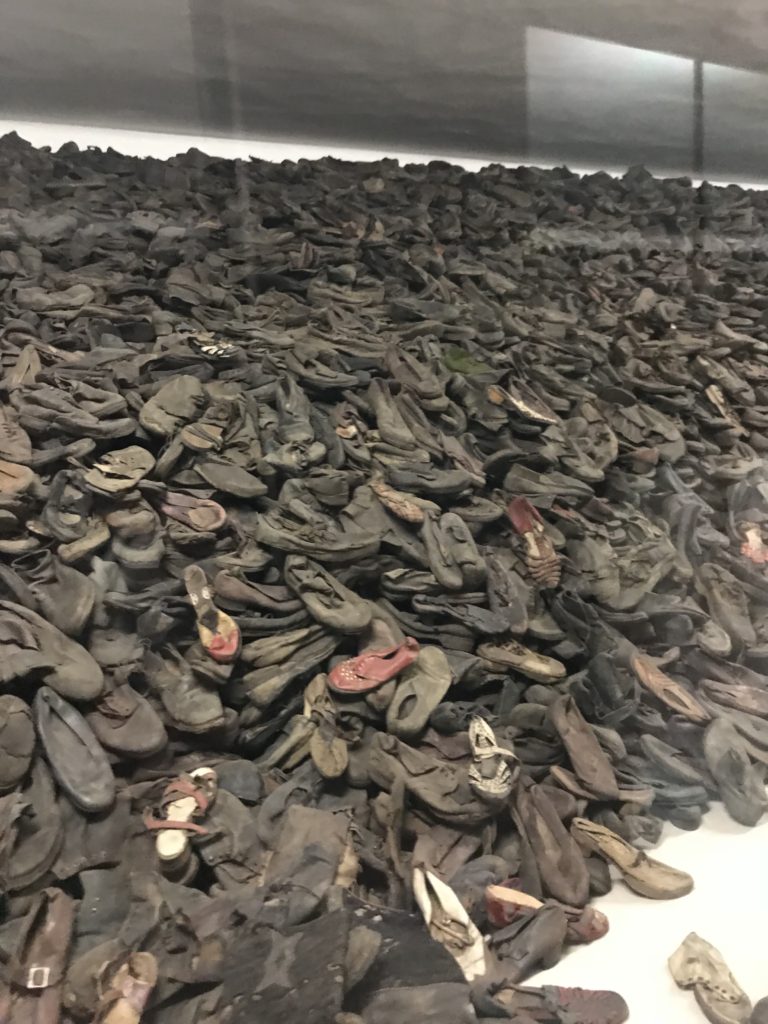

As you move through the museum, you see not only photographs of the brutality inflicted on the people at Auschwitz and other concentration camps, but also piles of shoes, eyeglasses, prosthetic limbs, suitcases, cook wares, etc., piled up in quantities that speak to the 12 million people the Nazis killed. One of the worst sights was of hair.

Every woman who went through the gas chambers of Auschwitz was shaved, after being gassed. The hair was used to make pillows, rain coats, and various other cloth-based items, for military use. Several long braids of hair are shown on top of a roll of material made from human hair. This was not enough to drive the point fully home though, as after seeing the material made from hair, we were walked past a pile of human hair with braids from around ten thousand women. It was a pile that turns the stomach, and yet it was a pile of hair that was in a warehouse at Auschwitz, found when the camp was liberated.

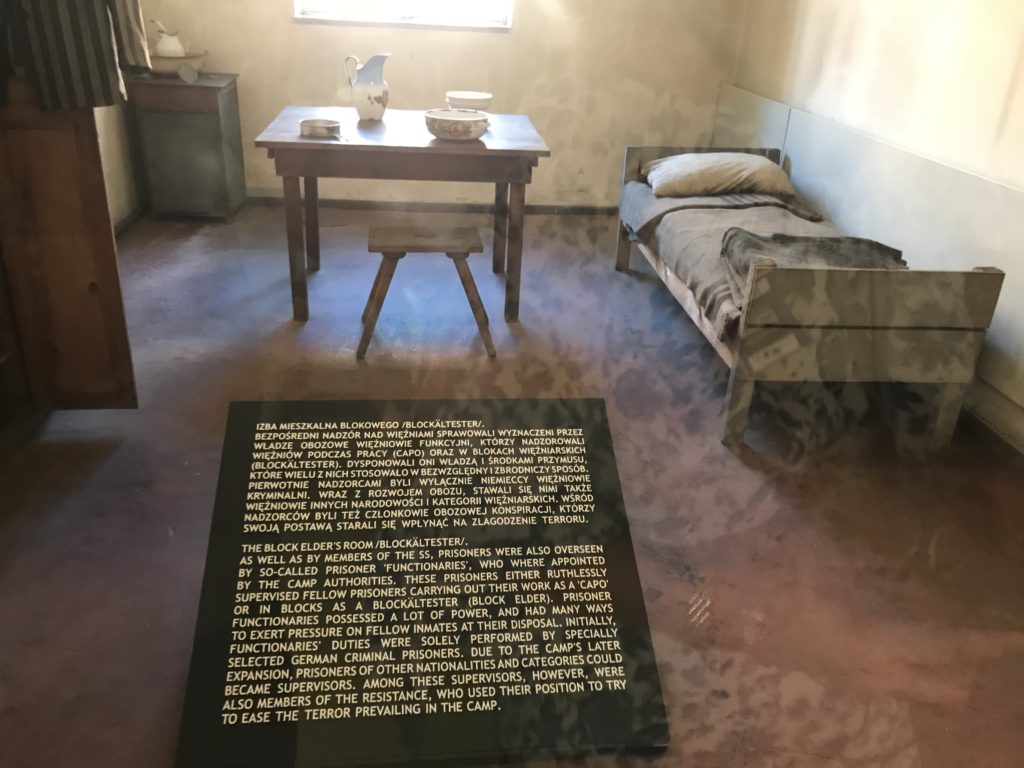

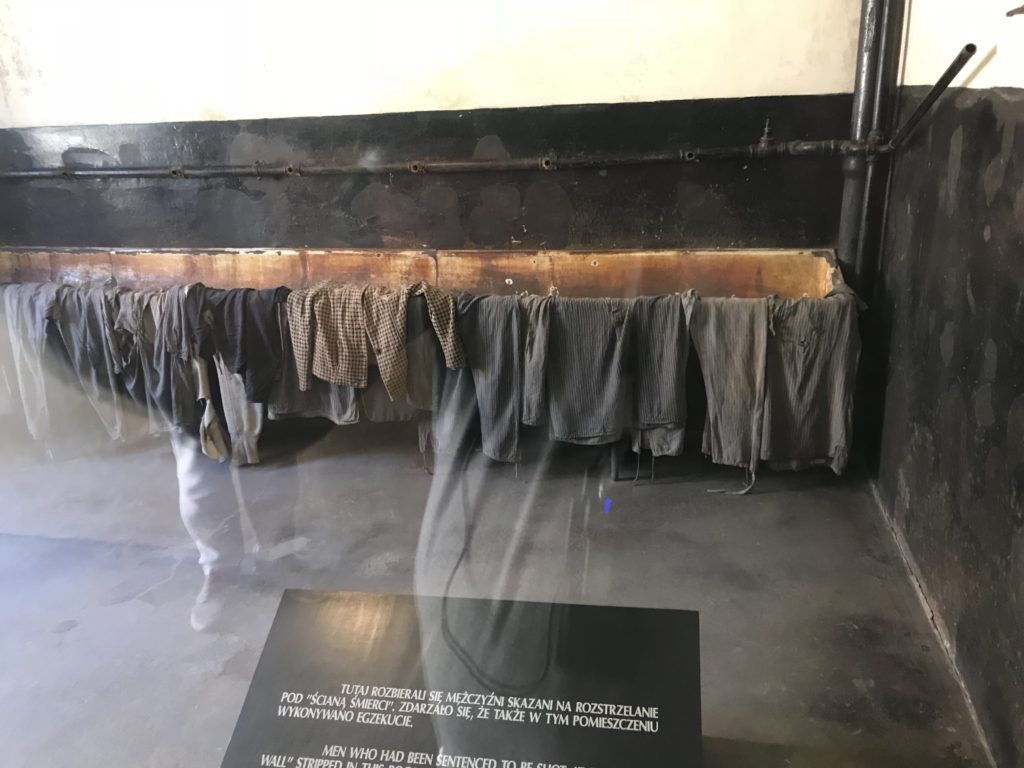

We were not allowed to take photos of the hair, and I did not want to take photos of some of the other piles, but my wife instructed me to take some, and you’ll see those in this article. I took more care in photographing the every-day living conditions of the Auschwitz I inmates, and of the punishment facilities for inmates who were punished without simply being shot on sight. Even at Auschwitz I (a work rather than a death camp), the brutality was all around us.

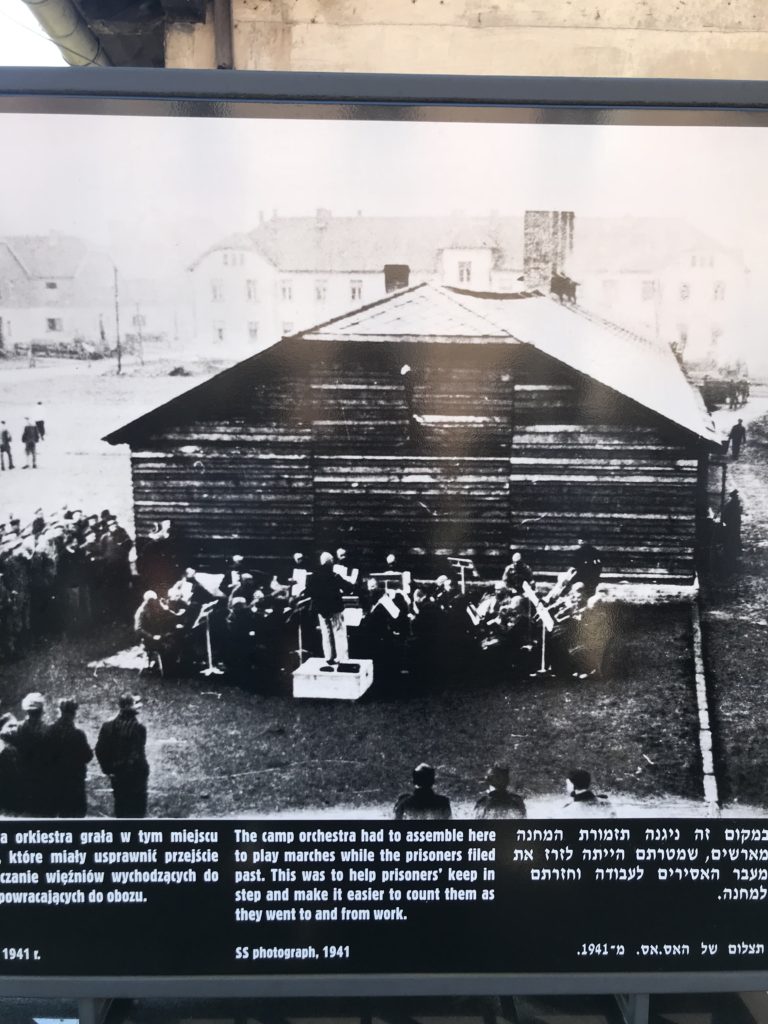

Conditions changed between 1941 and 1944, as more and more people were sent to Auschwitz (thanks largely to its centralized location within Nazi-dominated Europe). Auschwitz I, at one time, housed 20,000 people – around four times what it was designed to hold. Prisoners worked around 10 hours a day, and held two roll calls, in which everyone had to be counted, including the dead – which means that if someone died during the day, others had to carry that body around until evening roll call.

Roll calls were often used to punish the camp, with one roll call lasting 19 hours. If you want to know what that would be like, try standing at attention for two hours, and then, as the pain starts to grow, imagine how bad it must have been seventeen hours further in.

Auschwitz I appeared capable of adequately feeding the number of people it was designed to hold, but there was no way it could have adequately fed 20,000 people, even had the Germans wanted to adequately feed them, and, of course, working them until they died was one of the main points of the place.

Next to the jail (where inmates were punished) was Joseph Mengele’s ‘hospital’, where the infamous doctor conducted sickening experiments on inmates, and particularly on twins. The inside of this building was not a part of the tour, and thankfully the tour did not go into detail over everything Dr. Mengele did (though if you go to Dachau you’ll see quite a bit on that).

Finally, we walked through the primary gas chamber of Auschwitz I, and got a feel for its layout. This was important, as the Germans did what they could to destroy Auschwitz II – Birkenau, before they retreated from it. The gas chambers and furnaces of Auschwitz II – Birkenau were destroyed. The gas chamber and furnace of Auschwitz I was, at the end, used as a bomb shelter for the SS troops stationed at Auschwitz (the SS barracks being next to it), and as such the structure survived.

This ended our tour of Auschwitz I.

We were pretty spent after standing in line for two hours, and then walking around on the tour for between two and three hours. I left feeling sad and bewildered. We rested in the grass outside the compound for about 20 minutes, waiting for a bus to take us to Auschwitz II – Birkenau.

Auschwitz II – Birkenau is a much more basic structure, but also much larger, designed to hold 90,000 people (it held as many as 250,000), and there is nothing I can do, including sharing photos, that could possibly prepare you for the vastness of the site.

Auschwitz I was built in the suburbs of Oswiecim, Poland, and though some Poles were kicked out of their homes to make room, the camp was centered on an existing Army base, so relocations were limited. Auschwitz II – Birkenau was centered in the center of Birkenau, Poland, and the city was torn down to make room. Bricks and other building supplies from the city were re-used to build the first half of the camp.

The Polish people who were kicked out of their homes were not compensated in any way. They were simply told to leave, and if they resisted, they were shot.

You can’t really tell it from the photos, but when you are standing near the railroad tracks, photographing to the left or right, each side is only half the camp. From the center, where trains were generally unloaded, the site seems to go on forever.

Rudolf Hoss designed Auschwitz II – Birkenau, and he discussed the design, in detail (with the detachment of an engineer) at the Nurnberg War Trials. He said that he expected the unloading of the trains, and the sorting of people into workers and non-workers, to be the bottleneck determining how many people could be killed. Initially there was only one set of train tracks going into the camp, and they went all the way through to the back, where the gas chambers were located.

Over time, as the camp became busier (and the second half was built – out of wood rather than brick), the single track coming into the camp was split into three, such that though only one train could go through the gate at a time, three could be unloaded. Hoss designed the gas chambers and the furnaces around the notion that the camp would hold around 90,000 people, and that half of the people who entered would be assigned to work details (the other half being immediately gassed). The camp then, once full, would kill twice as many people as necessary to keep 90,000 workers.

What Hoss did not take into account was that the Germans would periodically send workers through inspections, and kill large numbers of those who had previously been spared for work. Workers already in the camp were literally competing against those just arriving, with only the 90,000 strongest available being allowed to live, and Hoss underestimated the rate at which workers already in the camp would be sent to the gas chambers.

Hoss also did not foresee the camp holding as many as 250,000 people.

Hoss testified in Nuremburg that had he known that the furnaces, rather than the trains, would be the bottleneck, he would have designed the camp differently, and believed he could have made the camp between three and four times as efficient – meaning that he could have killed Jews three to four times more quickly.

As you walk from the sorting area (where Jews were separated into those who would work, and those who would immediately be gassed), to the gas chambers, you walk down the exact road that the 1.3 million people estimated to have been gassed at Auschwitz II – Birkenau marched to their deaths.

At the end of the road are two blown-up gas chambers / crematoriums. Prisoners were marched to the back of the buildings, and told to go through doors into the basement. The first room had numbered hooks on the walls, and the prisoners were told to undress and head to the ‘showers’, remembering their numbers so that they could collect their belongings after having showered. The prisoners, then naked, were sent into what they were told were showers. Some were even given soap and shampoo.

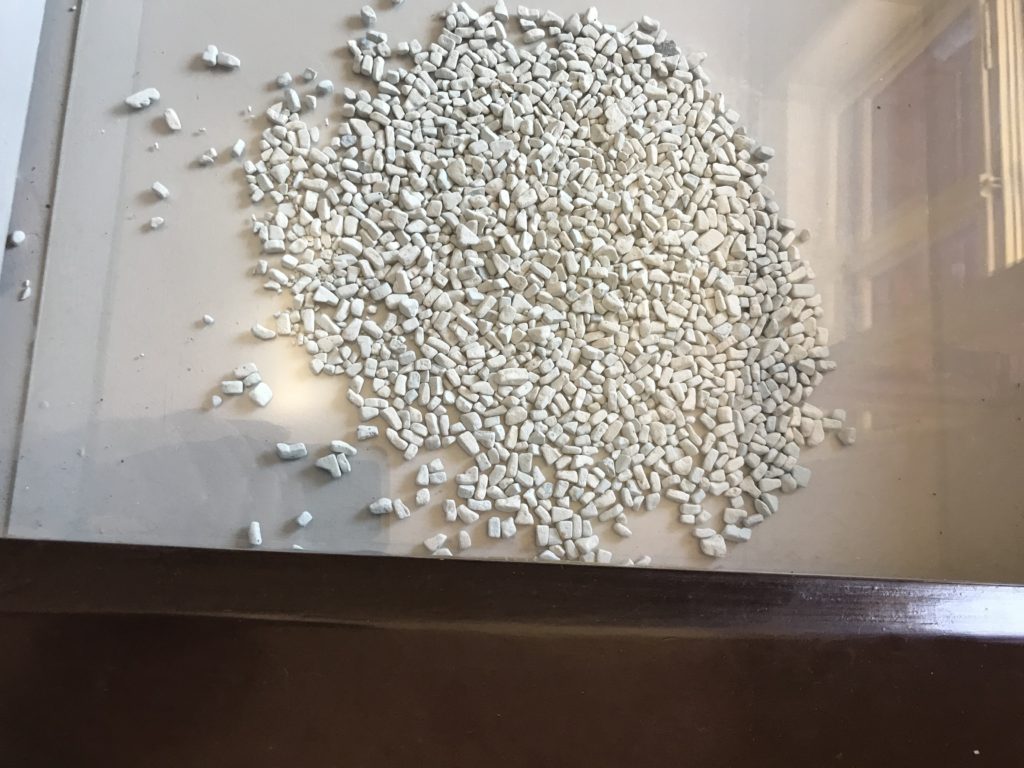

Once all of the prisoners were in the showers (the shower could hold about 700 people), cyanide crystals were poured in from the roof, and the vents were sealed. It took about twenty minutes for everyone inside to die.

After about 20 minutes, the doors were opened, and the bodies were carried upstairs to the furnaces, where they were cremated. Their ashes were used as fertilizer for farming, and were also dumped in rivers and ponds throughout the area.

Between the two large gas chamber / furnace buildings stands a memorial to those killed.

After seeing the gas chamber ruins, our tour walked back up to the front of the complex, where we saw the living conditions, which can only be said to have been horrific. Workers were not fed enough to survive, and as they died they were simply replaced by more workers. The entire compound of Auschwitz II – Birkenau was designed to kill as many people as quickly as possible, and the fact that the designer said he would have liked to have had the chance to make another camp three to four times more efficient should make one’s blood curdle.

What made my sadness turn to anger was not the living conditions, nor even the gas chambers. It was the sheer size of the site, with barracks that seemed to go on forever, all around me. I could imagine Jewish people marching to the gas chambers, not knowing they were about to die, and I could imagine the workers, every day knowing what had happened to the people they loved, and also knowing that as soon as they were no longer stronger than new people just entering the camp, they too would be killed.

The size of the place angered me. It angered me because there are people today who would be only too happy to read up on Rudolph Hoss, and design something three to four times more efficient. It angered me today because, in spite of the fact that we have learned nothing, our ability to kill continues to grow.

Auschwitz, today, really is almost a theme park to our species’ special ability to kill our fellow mankind. People say that we must never let anything like that happen again, and yet it is happening, even as I write this, today.

If we fail to learn from history, and start to prevent these kinds of atrocities from occurring (and stop them where they are currently occurring), our fear should not just be that we will repeat history and see these things again. We must fear more than that. Rudolph Hoss did learn from history, but rather than learning that killing is wrong, he learned that he could kill far more efficiently than he did at Auschwitz II – Birkenau. You may have noticed the hangman’s platform next to the gas chamber in my photos of Auschwitz I. That was built after the war, specifically to hang Rudolph Hoss, and unlike so many other German war criminals, Rudolph Hoss died right next to where he had killed his victims, within a couple hundred meters of the house he lived in, while commandant of Auschwitz.

Who will hang the people committing such atrocities today? Who will teach the people waving Soviet flags, and wearing Che Guevara shirts, that they are asking for the same atrocities tomorrow? Who will force us to learn from history such that we do not continue to repeat it?

I fear no one will. There are still too many communists, and they are unwilling to see the parallels between Auschwitz, and similar facilities everywhere communism has been tried.

There are still too many people who are unwilling to learn, and as a result, Auschwitz will be repeated.

[…] posted recently about how Auschwitz was not only a testament to the past, but also a warning about t… – and a warning not only about racist totalitarianism, but about any form of totalitarianism […]

[…] to a gulag, but I have been to two concentration camps (Dachau and Auschwitz), and I wrote about my recent trip to Auschwitz here. People were sent to concentration camps for different reasons than they were sent to gulags, but […]