Nothing is more central to a subject than Supply, Demand, and Scarcity are to Economics. The entire field is based upon these principles. They happen whether we recognize them or not. There are literally hundreds of Economic texts to describe these actions, but maybe a ‘readers digest’ reminder is in order, as folks seem to misplace their common knowledge of these things. Let’s dig.

Scarcity

All assets are scarce, even those with a large, available quantity. Scarcity just means that items have a finite quantity, and that quantity, once spent, cannot be spent again. Of course, the two most obvious applications of scarcity are time and money. Time spent doing ‘A’ cannot be re-spent doing ‘B’. Money spent on item ‘C’ is no longer available to spend on item ‘D’. If either of these were infinite, our entire universe changes. We would then have ‘time’ to practice any endeavor enough for proficiency. We would not care the ‘cost’ of anything, as our infinite cash supply can buy…well, everything. But, back in the Real World, scarcity is quite the unforgivable constraint on everyone. All lifespans have beginning (birth) and end (death), and the space between those events is quite finite. And even the mega-wealthy can outspend enormous sums, although ‘enormous’ is relative. While they might have the resources to dwarf normal budgets and spending wants, they still have limits. On that same track, the things the mega-wealthy BUY are finite—there are only so many available tracts of land, modes of transportation, buildings, entertainment choices, and such for them to purchase. See ‘Supply’ below.

Supply

‘Supply’ is the quantity of a good or service available. As mentioned above, Supply is finite, even if it is a VERY large number. The reason? The resources to make things are finite, and if you use them to create item ‘C’, there are none left over to make item ‘D’. This sounds like a minor thing, but it really isn’t. Allocation of resources to make the optimal number of all goods is a great determining factor in the standard of living available. Using too many resources to make a glut of one item usually leads to a shortage of another. In Capitalist economies, ‘price’ is the major factor in resource allocation—when the price goes up, more producers voluntarily enter that market to take advantage of profits; when the price goes down, consumers voluntarily buy more of an item, leading (eventually) to a shortage, higher prices, and back again. It is a never-ending dynamic of producers trying to optimize their profits, consumers trying to optimize their spending dollar. In centrally-run economies (Socialism, Communism), price is not the driver: it is government decision that determines how many of everything to produce. That is also why such economies fail: they do not have enough information to optimize planning, and such plans are almost never timely enough to work well. But in any type of economy, it is a constant: Supply requires spending assets to create the quantity of goods available. It is an intentional action to create anything—it does not happen by accident. Someone decides to make more of something, either forecasting a need or a want for that thing. Important point: just because someone makes something, that does not mean that there are consumers willing to buy that new production at the price stated by the maker.

Demand

‘Demand’ is simply the accumulated quantity of consumers’ desire to buy something at any point in time. Demand is a completely independent thing. Demand for a good or service has no rules: no logic, no rhyme or reason. When a company forecasts Demand, it is a guess, plain and simple. They are hoping the future acts somewhat like the recent past, but that is also a guess. Consumers are fickle, with unique spending wants and needs. And, as long as there are multiple suppliers of a good (non-monopoly), consumers may buy from vendor 1, putting pressure on vendor 2 to either make a better product, or price it lower. A great example of unexplained Demand: toilet paper during the pandemic. Usage rates of that product did not change a bit. But consumers hoarded the normal Supply of toilet paper, anticipating a shortage, thereby CREATING a shortage! There was very little reason for such thinking: production levels never changed, distribution never wavered. But stores that formerly had AISLES of toilet paper now had empty shelves! There was no real logic for the new shortage, but name-brand, high quality paper simply wasn’t available, in stores or the normal online vendors.

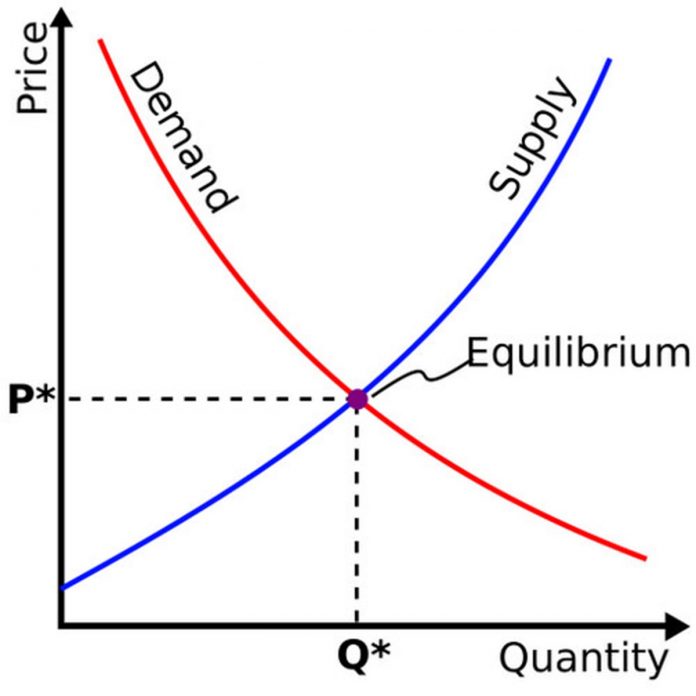

Results

Supply and Demand curves are usually depicted as a large ‘X’, with the line that slopes from low to high, left to right, as Supply, and the line from high to low, left to right, as Demand. For nearly all products (those not of a monopoly), as the quantity of Supply increases, the Demand decreases, and vice versa. Where the two lines intersect is the optimal price, where the same amount of Demand is satisfied by the same amount of Supply. Again, this is a ‘readers digest’ summary of these dynamics, but the basics prevail: Scarcity, Supply, and Demand.

Welcome!Log into your account