Why does a head of iceberg lettuce cost $1.28 (here in TX,

today)? Why is it not $.25? Why not $5?

Why does a head of ‘organic’ iceberg lettuce cost $2.26, at the same

store? What sounds like an easy answer

is quite complicated—and is a very good example of how Capitalism works. Let’s dig.

To get the head of iceberg lettuce, or its organic relative, to market, many

pricing influencers have already taken place:

1. The farmer(s) had to decide a growing

season ago to commit valuable land, fertilizer, weeding, water, and such to grow

lettuce (organic or otherwise). If they

are a large concern, they likely have labor to pay, machinery to buy and

maintain. They have to decide to grow

lettuce, rather than green beans, corn, soy beans, or whatever, in that

particular field. They have to

decide: is it worth the extra cost to be

‘organic’? Are there FDA inspections to

be done? Do they take their own harvested

crop to the local farmer’s market, or do they sell to a wholesaler? Does the wholesaler represent a grocery store

chain, that may or may not add an additional level of inspection? Does the farmer have enough resources to meet

the scheduling demands of harvest? Is

the price offered to the farmer worth all of the above costs? I am likely dramatically over-simplifying

this process, as I am not a farmer—a farmer may read this and think I missed

1,000 major decision-points. And he’d be

right. No one but a true farmer by trade

knows the ins and outs better—no matter what Michael Bloomberg said to the

contrary.

2. How to get the lettuce from where it

is grown to where it is sold? This is

likely a more complicated answer than first glance would assume. Does the farmer hire out that

transportation? Does he buy trucks and

such, taking a long-haul approach? Does

he take his crop to point A, knowing that someone else will take it from point

A to point Z? Many different scenarios,

with many different pricing factors. One

thing is certain: none of that travel

happens for free. So, transportation is

a factor in the final price, but really as a profit limiter for the farmer or

seller, depending upon who pays for what.

3. How good was that applicable growing

season? Was there adequate rain or was

secondary irrigation necessary? Was

their too much rain? (I have no idea how

much is ideal for lettuce—STILL not a farmer).

Did the farmer experience loss due to wild animals eating or otherwise

ruining crops? Did the insecticides used

do the trick, or did some new strain of bug hit his field? Was the fertilizer chosen adequate? Did the fertilizer, along with the existing

soil condition and health, produce the expected crop volume?

4. How many other growers decided

lettuce was the thing to grow? Is the

final supply to market greater than or less than expectations? Did a new big grower influence the entire

market? Did a big grower stop growing

lettuce, making each head possibly a bit more valuable than otherwise?

5. Do people still want to buy

lettuce? Has there been bad publicity,

causing folks to buy less? A nasty rumor

is just as damaging as a real issue. Do

the sellers have enough special shelf space available to market enough of your

crop? Is the buying process too quick, causing

shortages, or too slow, causing spoilage?

Most of those issues are absorbed by the final seller, but only for this

season—big changes may effect future wholesale buying volume decisions.

6. Is ‘organic’ still worth it? Are there enough buyers to warrant the

increased process costs, or was that an expired fad?

The interesting thing to note is that all 6 points above

have to be forecast months, if not years, in advance by the farmer. If he forecasts incorrectly, or if outside

influences change unexpectedly (weather, labor, demand, competition, etc.), the

farmer can experience HUGE losses pertinent to that specific crop. Now, it could be that the farmer diversifies

what he grows, and a loss in crop A may be absorbed by a windfall in crop B

(once again, I’m NOT a farmer). But that

level of planning and pure chance is beyond most folk’s ability to make it

work.

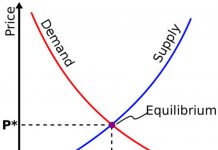

In summary, Supply and Demand still rule Capitalist ventures, none more so than

farming. But the devil is in the details,

as always. When we see the $1.28 per

head price, that is the RESULT of everything else. That price, or an increase or decrease in

that price, will absolutely impact future farming decisions. In a Socialist or Communist economy, farmers

are usually told by government what to grow.

But in Capitalism, each farmer decides what his best guess is for his

own future. Maybe it’s time to raise

cattle, and abandon the farming thing altogether…