According to liberal Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, regarding Roe v. Wade, Roe was not a good idea. She believed that Roe was not constructive to the overall acceptance of abortion. Said the Notorious RBG, “My criticism of Roe is that it seemed to have stopped the momentum on the side of change”. Stating further, “Roe isn’t really about the woman’s choice, is it? It’s about the doctor’s freedom to practice…it wasn’t woman-centered, it was physician-centered.”

Though not explicitly stated, Ginsburg believes legislation should have been the way to change abortion availability. That decisions for abortion legality should be left to states. In her critique of Roe, the ruling should only have overturned the Texas law in question, Ginsburg further suggesting, “…to fashion a regime blanketing the subject (abortion), a set of rules that displaced virtually every state law then in force.” That is to say that by force majeure, or superior force, all related state laws throughout the United States were overruled by Roe. Not just Texas.

Say what you will regarding her judicial philosophy, in this case, she’s spot on constitutionally. It’s an originalist position to leave political changes to the states.

This is not what happened in Roe v. Wade.

The genesis of Roe was in the form of Norma McCorvey. She was the Roe, Jane Roe, in Roe v. Wade.

The life of McCorvey in the 1960’s was certainly no dream. She was married at 16 to a man who she stated abused her. Following her divorce in 1965, she was an alcoholic and she became pregnant and gave birth to her first child. Through some rather underhanded means, her mother tricked Norma in to signing adoption papers, giving custody to her mother, under the guise that these were just insurance papers. A year later, McCorvey became pregnant again and decided she should give this child up for adoption.

Forward to 1969 and Norma McCorvey is again pregnant. This time she did not want to bring the child to term. As a citizen of Texas, where an abortion could only be performed when the life of the mother was in danger, McCorvey could not find a facility to perform her abortion. Her life was not in danger, nor a victim of a rape, though she attempted to claim this. She simply did not want this child.

Enter activist lawyers Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington. Lawyers that had been looking for abortion cases to litigate. Up to, and even following, the Roe v. Wade ruling, McCorvey was, by her telling, an unwitting victim. She was not looking to be the subject of a transformative court case. McCorvey simply wanted legal representation as she sought an abortion.

Despite the Roe v. Wade ruling three-odd years later, Norma McCorvey never did get that abortion and also gave this child up for adoption.

Who is ‘Wade’?

While Jane Roe was a pseudonym for Norma McCorvey, the the plaintiff in Roe v. Wade was Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade. Wade was elected as a Democrat to the post of D.A. in 1951. A tenure that continued through 1987. During that time, in addition to the abortion case, Wade also prosecuted Lee Harvey Oswald gunman, Jack Ruby.

Wade’s legal career had a number of well publicized cases as he was also known to be an aggressive litigator. Some suggested he was overly aggressive with a ‘win-at all-cost’ approach that subsequently led to a number of conviction exonerations. In this case, his job was simply to defend the existing Texas abortion law.

It’s important understand that given the consequence of Roe on society and its universal recognition throughout America, this case involved very real people. Flawed people, people with agendas and mixed moralities.

What then was the basis of the original Texas Roe v. Wade lawsuit?

The lawsuit named Henry Wade as the defendant and asked that the Texas laws limiting abortion be rendered unconstitutional as well as injunct the District Attorney from further prosecuting alleged crimes as a result of the Texas Abortion Laws. In the complaint, it was stated, “…the Texas Abortion Laws must be declared unconstitutional because they deprive single women and married couples of their right, secured by the Ninth Amendment, to choose whether to have children.”

The named Texas Abortion Laws were Articles 1191-94 and 1196 of the Texas Penal Code. These laws set forth penalties for health care providers that perform abortions outside of Texas regulations, or for furnishing information regarding the procurement of an abortion. Recalling Ginsburg’s assessment that Roe was ‘physician-centered’, this is true. These statutes assigned legal jeopardy to the medical professional. The person seeking the abortion (e.g. – Ms. McCorvey) did not have any legal jeopardy within these statutes.

With Coffee and Weddington’s aim to overcome a law they saw as restrictive, the mechanism chosen to underpin the lawsuit was the Ninth Amendment. This is significant to the success of Roe v. Wade as it provided something of a constitutional loophole. The Ninth Amendment in the Bill of Rights states, “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

James Madison reluctantly authored the Ninth Amendment. Madison believe that the powers granted the federal government were clearly enumerated in the Constitution proper. That there should be no need for a Bill of Rights. Federalists, like Madison argued, “…that the Constitution did not need a bill of rights, because the people and the states kept any powers not given to the federal government.” However, in order to ratify the original Constitution, several states required that a so-called Bill of Rights be put in place to ensure individual rights.

Even though Madison did not think the Bill of Rights was needed, he crafted the Ninth Amendment in order to ensure that the government would not construe the Bill of Rights as the only rights afforded citizens.

Prior to 1965, the Ninth Amendment had nearly no judicial history. That’s 174 years of nothing more than legal passing references. This amendment was really a simple backstop to the rest of the constitution as Madison had intended. It was not meant to be constitutionally significant.

That was until 1965 when the Supreme Court ruled on a case called Griswold v. Connecticut. In Griswold, the court ruled on Connecticut’s prohibition of contraceptives. The ruling was 7 to 2 for Griswold, agreeing that the state could not prohibit married couples that were heretofore unable to obtain contraceptives. At the core of Griswold was the court’s interpretation of a so-called right to privacy.

There was only one problem; there is no right to privacy in the Constitution or the Bill of Rights. The constitutional documents state nothing about actual privacy.

So tenuous was this newly asserted right to privacy that when writing the supporting Griswold opinion, Justice Douglas stated, “The foregoing cases suggest that specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance. Various guarantees create zones of privacy.” (emphasis mine)

Though the idea of ‘penumbras’, or implied rights, is not exactly new in judicial decisions, in this case, the application of an implied right has to be considered. In Douglas’ assertion of ’emanations’, he’s essentially saying that though some rights can be implied, when not explicitly stated in the Constitution, that we can go one step further than just that one implied right. That you can stack one implied right on top of another implied right. Emanations from a penumbra.

The Roe v. Wade suit references the Griswold decision thusly:

“[T]he Ninth Amendment shows a belief of the Constitution’s authors that fundamental rights exist that are not expressly enumerated in the first eight amendments and intent that the list of rights included there not be deemed exhaustive.” (emphasis mine)

Further stating:

“The Ninth Amendment simply shows the intent of the Constitution’s authors that other fundamental personal rights should not be denied such protection or disparaged in any other way simply because they are not specifically listed in the first eight constitutional amendments.” (emphasis mine)

Herein lies the greatest flaw within the Roe v. Wade decision. It’s often been said that Roe was ‘bad law’ by stating that abortion was not in the Constitution. True, and it would be silly if it was true. The question is not a matter of abortion’s constitutionality. If this were the question, any medical procedure should be considered in terms of legality. Immunization laws could be rendered unconstitutional if the procedure’s legality were the only consideration.

In Justice Henry Blackmun’s majority decision, he states, “This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment‘s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment‘s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” (emphasis mine)

Summing Blackmun’s majority opinion (from highlights); ‘this right of privacy founded in the Fourteenth Amendment or in the Ninth Amendment is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy.’

The Fourteenth Amendment being the equal protection clause.

The Texas Abortion Laws contained multiple offenses for which a physician could be charged. Of them is Texas code 1192’s ‘accomplice liability’. That a physician providing information on where a patient could obtain an abortion would be construed as an accomplice of an illegal act. Had the Supreme Court simply struck down this section, the decision arguably would have been on a more solid footing. It’s a private conversation.

However, the Roe decision asserted legality of an abortion as a matter of privacy. In his dissent, Justice Rehnquist disagreed, “I have difficulty in concluding, as the Court does, that the right of “privacy” is involved in this case. Texas, by the statute here challenged, bars the performance of a medical abortion by a licensed physician on a plaintiff such as Roe. A transaction resulting in an operation such as this is not “private” in the ordinary usage of that word. Nor is the “privacy” that the Court finds here even a distant relative of the freedom from searches and seizures protected by the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, which the Court has referred to as embodying a right to privacy.”

It would seem confusing that the decisional crux had shifted from the Ninth to the Fourteenth Amendment, but this is how you get emanating penumbras.

Simply making privacy a right using only the Ninth Amendment would then make anything a right (as you now see pervasive on the left’s wont to render every leftist idea as a ‘right’). In addition to the Ninth Amendment, there still must be another pillar to support privacy as a constitutional right. This came from the Fourteenth Amendment.

But doing so makes Roe a Rube Goldberg-type decision. A Rube Goldberg machine is an amusement device that relies on a previous action to start, or kick off, the machine’s next action.

In order for privacy to be a general right, that right must be found elsewhere. Insert the Fourteenth Amendment.

Further in Rehnquist’s dissent, he continued, “But that liberty is not guaranteed absolutely against deprivation, only against deprivation without due process of law. The test traditionally applied in the area of social and economic legislation is whether or not a law such as that challenged has a rational relation to a valid state objective.”

A valid state objective, as suggested by Rehnquist, is in support of a state government to enact laws, even if application of the law would have differing impact on constituencies; so long as the law meets the state’s overall policy goals. Here, the Justice points out that a right is not absolute. Only that an enumerated or implied right be provided due process if the right is in question.

The weakness of the Roe claim is that the right to an abortion, as a matter of privacy, is absolute. No right is absolute, even if enumerated in the Bill of Rights. Rights have limits.

The underlying constitutionality of Roe’s majority decision is at least arguable, if misguided, but the application within the decision simply crosses the line from judicial interpretation to legislating from the bench.

The Roe decision should have simply rendered the Texas laws as either constitutional or not. At which point, Texas would be left to craft a new law or simply rescind the existing laws. This is not what occurred in the majority decision.

In section 11 of the majority decision, “For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health.” Per the above text within the Roe decision, the second and third trimester were to be regulated.

Why is this a problem?

The majority opinion is not simply an interpretation of the law but went further to law application. By definition, this is legislating from the bench. Such guidance squarely oversteps the separation of powers. The water’s edge for a decision is whether or not a case in front of the court passes constitutional muster.

The risk of exceeding simple law interpretation is that doing so circumvents the democratic process. What laws get created and how they are implemented are specifically the responsibility of either the states or federally elected government officials. The ‘bad law’ of the Roe decision was the overstepping of judicial power and detailing what’s legally allowed in abortion availability. That being the trimester concept and how that concept is medically applied.

In the Roe decision, the Supreme Court assumed powers it did not have by using an implied privacy right as a gateway.

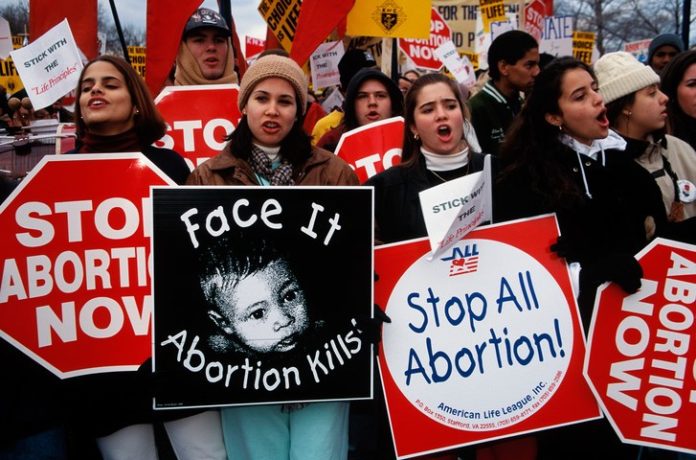

Several states are considering bills that intend to limit abortions. Florida is seeking to define the fetus as an ‘unborn human being’, whereas many other states, such as Mississippi and Ohio, are considering heartbeat bills. The intent of ‘heartbeat’ bills is to establish a limiting of abortions at the point of a heartbeat, which is generally at six weeks.

These bills may have constitutional implications.

With a recent shift in the court to a more conservative and originalist composition, it would seem more likely now that a significant abortion case would be heard. These bills are significantly more restrictive than previous abortion laws and clearly beyond the guidance of Roe as well as the subsequent decision regarding fetus viability (via the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision). In Casey, it’s generally accepted that viability is at approximately 24 weeks.

Critics of the recent spate of ‘restrictive’ state bills suggest a purpose in doing so, “… introduce flagrantly unconstitutional legislation…fully aware that those laws would be challenged by pro-choice groups.” Given the tactics of the left regarding judicial activism, the pro-life ‘flagrantly unconstitutional’ strategy seems a solid scheme. If there is any overturning or significant changes to Roe, Casey et al, it’s to be found in a challenge that specifically takes Roe head on. It’s simply a matter of what best facilitates the challenge.

Pro-choice groups fear the possibility that a SCOTUS decision would rule a fetus as human. Even though this is a highly unlikely ruling, this is a very real worry of the left. As a moral argument, there is a compelling argument in support for fetus-as-a-person at any stage of development.

As a constitutional argument, it should be a non-starter. Recalling the privacy justification (errantly) implied within Roe v. Wade, what other constitutional rights can apply to a fetus? Does the fetus need protection from the government for free speech? The right to bear arms? Illegal search and seizure? As a legal position, it is hard to confer a constitutional, legal right to an entity (unborn child) that cannot exercise them. Accordingly the Bill of Rights would be a poor mechanism to define personhood.

It’s more likely Roe will be overturned due to flaws within the original decision itself. The biggest challenge to which is the legal principle of stare decisis, or deferring to the precedent of previous judicial decisions. Many originalist/textualist jurists apply such a stare decisis methodology to judicial decisions.

Assuming the case before the court is compelling enough to overcome stare decisis, what is the best mechanism to overturn Roe?

The errantly applied right of privacy opened the door to Roe’s decision as a right but the real weakness is within the decision’s application of how abortion law is implemented (i.e. – the ‘trimester/viability’ concepts). Any case that addresses the viability guidance will more likely render a decision invalidating that portion of the original Roe, as well as the subsequent Casey decisions.

By doing so, the implementation of abortion law returns to the states which ultimately should be the goal. Overturning Roe in any form will not make abortion illegal. Nor should any judicial decision do this. The establishment of life or death legality is the purview of the legislative process. This returns the debate to constitutionally stable ground.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg recognized this with her inference that abortion was already trending towards broader acceptance up and until the Roe decision. Echoing her position in the Atlantic, Brooking Fellow Benjamin Wittes suggested, “One effect of Roe was to mobilize a permanent constituency for criminalizing abortion—a constituency that has driven much of the southern realignment toward conservatism. So although Roe created the right to choose, that right exists under perpetual threat of obliteration, and depends for its vitality on the composition of the Supreme Court at any given moment.”

As a postscript to the more than 45 years since the Roe decision, Norma McCorvey (a.k.a – Jane Roe) became a staunch Christian and pro-life advocate. Her conversion to pro-life came when she found herself examining a fetal development poster, “Something in that poster made me lose my breath. I kept seeing the picture of that tiny, 10-week-old embryo, and I said to myself, that’s a baby! It’s as if blinders just fell off my eyes and I suddenly understood the truth — that’s a baby!”

McCorvey’s revelation speaks to an emotional feature fundamental to the human condition; protection of the child. It reveals why pro-choice (pro-abortion) advocates have an intense opposition to laws requiring pre-abortion ultrasounds. Like McCorvey, the more human an unborn child appears in the womb, the less likely it is to be aborted.

And the more likely public acceptance of abortion diminishes in the democratic process.